on condemnation

terrorism, violence, and the question of palestine

Since the October 7th Hamas attack on Israel and the beginning of Israel’s subsequent bombardment of the Gaza Strip, I’ve been struggling with what, if anything, to write about the events of the last two months. I’ve started and abandoned more essays than I can count, semi-formed scraps of which currently live in various corners of my Notes app and my Substack drafts. Some of them, no doubt, will make their way into this essay—that is, if I even manage to finish it.

On the one hand, it feels like there’s nothing I can say that hasn’t already been said elsewhere, by others who are both more qualified and more eloquent than myself. In the face of all that has happened, words feel shamefully inadequate to capture the soul-crushing gravity of the present moment. I am cognizant, after all, of the fact that despite my best intentions, whatever I write here will amount in effect to little more than a drop in the ocean, yet another half-baked ‘take’ amid the already clamorous chorus of voices competing to have their opinions heard above all the rest.

On the other hand, when all is said and done, I’m a writer, and in a way my words are all that I have to offer. As insignificant as they may be in the grand scheme of things, it seems unthinkable for me to simply say nothing at all amid the horrors of recent weeks. I’ve been reflecting a good deal on that famous Kurt Vonnegut quote, the one where he says that during the Vietnam era, “every respectable artist in this country was against the war. It was like a laser beam. We were all aimed in the same direction. The power of this weapon turns out to be that of a custard pie dropped from a stepladder six feet high.” As defeatist as that quote may appear at first glance, it’s worth pointing out that nowhere in the interview where Vonnegut says it does he express regret for having used his platform as an artist to vocally oppose the war. He did so, not because it was going to change anything, but because it was the right thing to do. Because to stay silent would be the worst crime of all. That is, I think, a valuable lesson for writers, artists, and creatives of all stripes in the present moment—including myself.

These days, condemnation seems to be on everyone’s lips. In the nearly two months that have passed since Hamas launched its deadly attack on Israeli-controlled territory in the early hours of Saturday, October 7th, it seems that just about every mainstream public figure and institution in the United States—from political leaders to university officials to cultural institutions—has been competing to see who can condemn Hamas and state their support for Israel in the loudest, strongest, most emphatic terms. Even the NFL couldn’t pass up the opportunity to jump on the condemnation bandwagon, with no fewer than 14 teams issuing statements condemning the attack. (Is there anything more American than a football team condemning terrorism?)

A Google Trends search for the word ‘condemn’ shows a massive spike in the number of searches between October 6th and October 11th. Related queries which had the largest increase in search frequency, according to Google Trends, include “hamas,” “palestine,” “gaza,” and “do you condemn hamas.” That last question in particular—“do you condemn Hamas?”—has become something of a meme for its widespread deployment in increasingly inappropriate and irrelevant contexts. As with many memes, however, underpinning the sardonic humor is a kernel of truth—that condemning Hamas, and by extension condemning ‘terrorism’ itself, has become all but a prerequisite for participation in public life.

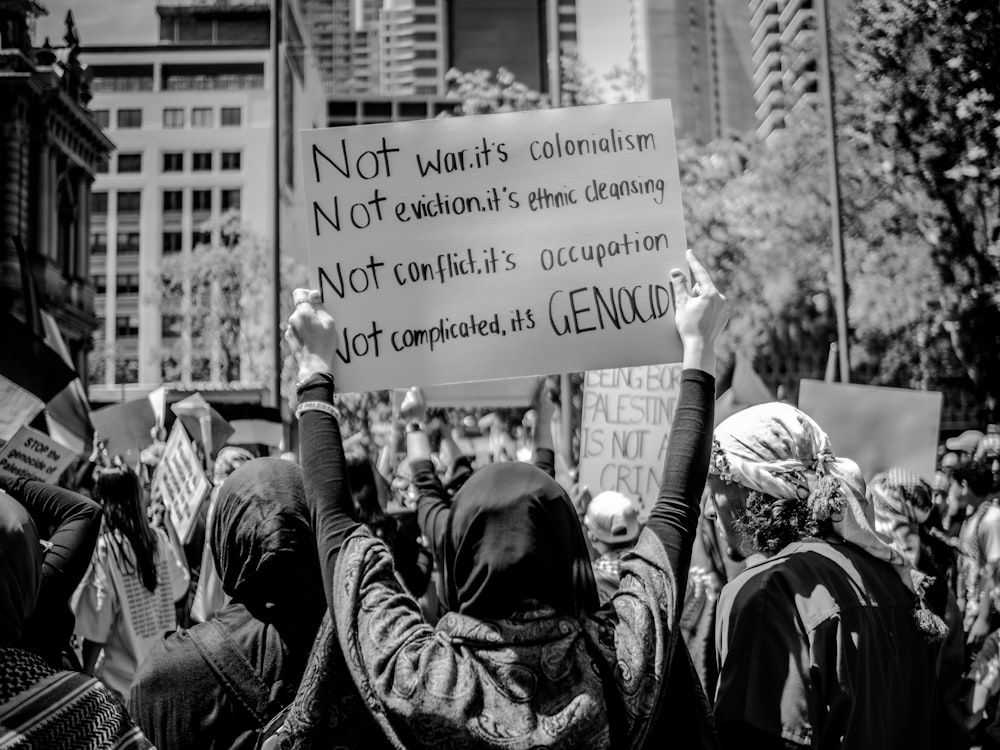

In the weeks since October 7th, the Overton Window on the issue of Palestine—an issue for which this window has always been alarmingly small—has narrowed more sharply and more immediately than at any other point in recent memory, in a curtailment of free expression rights that rivals the McCarthyism of the 1950s in its scope and severity. There is hardly any room left to call for a ceasefire or to criticize Israel’s genocidal assault on Gaza, let alone to raise the possibility that Palestinians may in fact have a right to resist the violence of occupation, colonization, and apartheid. Journalists and magazine editors have been fired, students have had job offers revoked, and award-winning authors have had their ceremonies cancelled. In the span of just two weeks, the advocacy group Palestine Legal reported responding to more than 260 instances of individuals’ “livelihoods and careers” being threatened for their solidarity with Palestine.

The prevailing wisdom among the vast majority of mainstream American media, political, and cultural institutions, as well as the centrist and liberal commentariat, is that there is no acceptable response to the events of the last two months apart from total and unequivocal condemnation of Hamas and the October 7th attacks. To question that prevailing wisdom, or even to discuss recent events in a way that does not reinforce its underlying logic, is to commit an unthinkable transgression.

But what, exactly, does condemnation mean in this context? What are we really saying when we say that we ‘condemn’ Hamas, or ‘terrorism,’ or any of the countless other bogeymen whose very existence we are told we must repudiate in the strongest possible terms? And why is it that when the conversation turns to violence, it is only ever the violence of Palestinian resistance that is framed in the language of condemnation, while the violence of Israeli occupation is downplayed and even justified as a regrettable but necessary evil—that is, if it isn’t being celebrated outright?

At the heart of the answers to all of these questions, but in particular the last one, is the notion that a clear distinction can be drawn between legitimate and illegitimate, justifiable and unjustifiable forms of violence. Broadly speaking, the mainstream liberal consensus holds that acts of violence carried out by state forces are presumptively legitimate, while those carried out by non-state actors are presumptively illegitimate. The former is referred to with sanitizing, supposedly neutral terms such as ‘defense’ and ‘armed force,’ while the latter is affixed with the most pejorative label of them all: ‘terrorism.’ To invoke the word ‘terrorism,’ within the conventional bounds of liberal discourse, is to bring the debate to a screeching halt—we can argue back and forth as much as we like over the question of whether this or that military operation was carried out in the right manner, adhering to the proper rules and protocols of legitimate warfare, but when terrorism enters the discussion, there can be no equivocation. There is no spectrum of acceptable opinions, no room for reasonable disagreement when it comes to terrorism. There are only two sides—those who are with the terrorists, and those who are against them.

But what are we actually talking about when we talk about ‘terrorism’? It’s worth pointing out that unlike war crimes, genocide, and crimes against humanity—all concepts whose invocation, like the invocation of terrorism, is typically intended to evoke a unique degree of moral shock and outrage—terrorism has never been clearly defined in international law. Different bodies define the idea of ‘terrorism’ differently—the U.S. Code, for example, defines terrorism as “premeditated, politically motivated violence perpetrated against noncombatant targets by subnational groups or clandestine agents.” Given its emphasis on “subnational groups,” this definition seems to exclude from the outset the possibility of terrorism ever being committed by state forces. By contrast, the United Nations General Assembly’s 1994 Declaration on Measures to Eliminate International Terrorism defines terrorism as “criminal acts intended or calculated to provoke a state of terror in the general public, a group of persons or particular persons for political purposes,” and explicitly notes that states may be “directly or indirectly involved” in “organizing, instigating, facilitating, financing, encouraging or tolerating terrorist activities.”

Like the UN’s definition, many definitions of terrorism, both legal and scholarly, are sufficiently broad as to include terrorist violence carried out by states. And yet, in popular discourse, the term ‘terrorism’ is used almost exclusively to refer to acts of violence perpetrated by non-state actors—insurgents, guerrillas, rebels, and the like. Even the criterion of who the targets of terrorism are—combatants versus noncombatants—is frequently ignored in favor of a simple distinction between state and non-state violence. For most people outside of activist circles, it would be all but unthinkable to imagine a soldier or a police officer being referred to as a ‘terrorist’. Why is this the case?

Part of the problem, I think, is rooted in the way we conceptualize the relationship between terrorism and politics. Most definitions of terrorism center on the idea that violence becomes terroristic when it is carried out in service of a political agenda or ideology. That is, for example, why the Sandy Hook Elementary School shooting is not widely considered to be a terrorist attack, while Anders Breivik’s 2011 massacre in Norway clearly is—the former lacked a clear ideological motive, while the latter’s neo-Nazi political agenda could not have been more plain.

But as with the idea of terrorism more broadly, this conception of the political seems to limit itself, at least in popular discourse, to the actions and motivations of non-state actors—as if the actions of states are not themselves inexorably political. On its face, the patent falsity of this claim is striking—there are, in fact, few things I can think of that are more political than violence perpetrated by the state. Was the Holocaust not political? Was Jim Crow or South African apartheid not political? The Korean War, the Vietnam War, the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan—were none of them political? If these grave historical injustices, in which states assumed the power to unilaterally decide who should live and who should die, who should have rights and who should not, weren’t political, then what is?

The problem, however, goes beyond the way we understand political and nonpolitical forms of violence. Our collective inability to conceptualize even the possibility of state terrorism is, I’d argue, due in large part to the fact that the very concept of terrorism as we understand it today is intended to distinguish between ‘legitimate’ and ‘illegitimate’ forms of violence, a distinction which is itself meant to uphold the state’s singular coercive power—what Max Weber famously referred to as the monopoly on violence from which the state derives its ultimate authority. In order to supposedly protect its subjects from violence and disorder, the state routinely employs violence—both threatened and realized—through institutions like the police, borders, prisons, and the military. In order to be justifiable, however, this violence requires an unjustifiable point of comparison. Without a concept of terrorism against which to juxtapose the regimes of violence, both everyday and extraordinary, that underpin its functioning, the modern state would lose its claim to a monopoly of violence—and therefore, would lose its very legitimacy.

The cultural anthropologist and postcolonial theorist Talal Asad, who has written extensively about the way terrorism and violence are conceptualized in the liberal tradition, argues in his 2010 essay “Thinking About Terrorism and Just War” that

“It should not be difficult, in this neoliberal world, to see how the prosperous Western states and third world militants occupy the same space of political violence. In this space terror is entirely normal: whether it be aerial bombardment (NATO’s ‘Enduring Freedom’) or suicide bombing, the destruction of whole cities and villages presented on television news (America’s ‘Shock and Awe’) or the killing of terrified hostages presented on video aired on television, the security state’s violent exclusion of would-be immigrants or the terrorist cell’s execution of traitors.”

Perhaps, then, this is simply a matter of asking the wrong questions. Instead of trying to discern what, precisely, is terroristic about the ‘illegitimate’ non-state violence that we call terrorism, what if we were to ask what is not terroristic about the ostensibly ‘legitimate’ violence of state forces? What, for example, is more inherently terroristic about a Hamas attack on a West Bank checkpoint than an IDF assault on a school or a hospital? Why is one a terrorist attack, and the other a military operation? Why is it considered an act of terrorism when Kashmiri militants fire on a convoy of Indian soldiers, but not when the U.S. military carries out a drone strike on a Yemeni wedding procession? Clearly, it isn’t that some of these examples are more political than the others—we’ve already established that the state is not above politics—nor is it that the so-called ‘terrorist attacks’ target civilians while the ‘military operations’ target combatants. The dividing line here, it seems, is nothing more and nothing less than the relationship of the violence in question to the state—and in particular, to the state as the bastion of imperial hegemony.

These questions are of more than mere academic importance. As an inherently loaded term, the word ‘terrorist’ is meant to evoke feelings of unmitigated hatred and revulsion, to place its subject outside the very bounds of humanity. Despite most Western states’ ostensible commitment to the rule of law and a rights-based legal order, these petty liberal concerns go out the window the moment we are confronted with the figure of the terrorist, who—like the pirate or the outlaw of yesteryear—functions in the modern Western cultural imagination as the personification of evil itself, an “enemy of all humanity” against whom any and all violence is warranted and even demanded. The question, therefore, of who we consider capable of being branded a terrorist—and why—could hardly be of any greater significance.

Palestine, of course, is an illustrative example of this. When Palestinians take up arms to resist colonial occupation, subjugation, and apartheid—as is their right under international law—they are called terrorists. But when Israel slaughters more than 14,000 Palestinians, it is merely exercising its so-called “right to defend itself.” As the writer Aaron Bady recently put it on Twitter:

“the basic (colonial) double standard of the Israel Palestine ‘conflict’ is that any Palestinian violence justifies any Israeli violence, but no Israeli violence ever justifies any Palestinian violence.”

As I highlighted above, to accuse someone of being a terrorist—or indeed, even of harboring terrorist sympathies—is to imply that they have surrendered some part of their humanity, and have therefore forfeited the rights and protections that would normally apply to a ‘full’ human being. They are fair game to be tortured, or indefinitely detained, or extrajudicially murdered—whatever it takes to neutralize the terrorist threat. Not only have the rules changed, but so has the game itself. Now, anything goes.

That is exactly what is happening in Palestine. Through a rhetorical framework that unquestioningly affirms Israel’s ‘right to defend itself’ against so-called ‘terrorism,’ Palestinians’ humanity is denied while that of Israelis is sacralized. The armor-clad IDF soldier wielding a machine gun at a border checkpoint is simply an innocent teenager, while the nine-year-old Gazan child playing football on the beach is a cold-blooded, Jew-hating terrorist in waiting. The former’s death is a tragedy; the latter’s a victory—or at best, an unfortunate but unavoidable casualty of war.

Israel claims that Hamas is the sole target of the current onslaught, that its goal is to wipe the terrorist threat that Hamas poses “off the face of the earth,” but from the standpoint of the IDF, Gaza is Hamas. Every refugee camp is in fact a terrorist training facility, every school and hospital a Hamas command center in disguise. When the President of Israel says, therefore, that there is no such thing as an innocent civilian in Gaza, we should take him at his word that this is exactly what Israel’s military and political top brass believes. The intention here—to wipe out once and for all those whom Israel considers “human animals” and “children of darkness”—could not be more clear. ‘Terrorism’ is simply the rhetorical shield behind which Israel hides to justify its genocidal violence.

In fact, however, the right of Palestinians to resist their subjugation by any means necessary, including by armed struggle, is grounded as clearly in international law as it is in the historical experience of liberation struggles around the world—from the Haitian Revolution to the decolonization of the Third World to the South African anti-apartheid struggle, armed resistance has always been a part of larger fights against violence and oppression. Even the American Civil Rights Movement and the Indian freedom struggle—both of which are frequently invoked by liberals as examples of liberatory movements that successfully eschewed violence—in fact incorporated armed resistance and self-defense alongside ostensibly ‘nonviolent’ forms of protest. For all of the hand-wringing and pearl-clutching about the existential threat that Israel supposedly faces from Palestinian ‘terrorism,’ the fact of the matter is that the ball is squarely in Israel’s court. If Israel wants to avoid armed resistance, it has both a legal and moral responsibility to end the occupation—full stop.

Of course, these facts don’t quite square with the cult of nonviolence which has come to dominate mainstream discourse, and which is routinely weaponized by self-righteous liberals to chastise oppressed people—Palestinians included—for resisting their oppression in the ‘wrong’ way. Enabled in large part by cynical misappropriations of figures like Martin Luther King, Jr. and Mahatma Gandhi, liberals have managed to turn nonviolence from a strategic political tool into an object of almost religious fetishization, treating it as a panacea whose unquestionable moral and tactical superiority renders it applicable to any and every situation of perceived injustice. In response to this cult of nonviolence, however, it’s worth considering a question that was once famously posed by Indian author and activist Arundhati Roy:

Can the hungry go on a hunger strike? Non-violence is a piece of theatre. You need an audience. What can you do when you have no audience? People have the right to resist annihilation.

The point about the necessity of an audience for nonviolence to succeed is crucial. It’s important to remember that the degree of international attention being paid to Palestine at the moment is the exception, not the rule. Most of the time, Palestine has no audience whatsoever—during periods of so-called ‘normalcy,’ the world turns a blind eye to the plight of the Palestinian people as they struggle under the crushing weight of Zionist occupation, apartheid, and colonization. Their screams go unheard, their calls for justice unheeded by the vast majority of those who are not already embedded in leftist spaces. Separated from the West Bank and Gaza by oceans and continents in addition to barbed wire and checkpoints, millions of people in the United States and other Western nations calmly go about their daily lives, blissfully unaware—or perhaps willfully ignorant—of both the scale of Palestinian suffering and their own countries’ complicity in enabling that suffering through the West’s unending support of Israel.

On the vanishingly rare occasions, such as this one, that the world does turn an eye to Palestine, it is virtually always a reproachful eye—condemning Palestinians for doing anything at all in the face of occupation and apartheid other than quietly sitting down and taking whatever comes their way. Deprived as they are of an audience to bear witness to their oppression, faced as they are with the prospect of annihilation as their everyday reality, it is both an absurdity and an insult to demand, as Arundhati Roy put it, that Palestinians go on a hunger strike. They cannot—they are already being starved.

All of this is to say that there seems to be no reason for any self-respecting leftist to take seriously the never-ending Zionist demand that we condemn Hamas—and ‘terrorism’ more broadly. If the chorus of voices clamoring for our condemnation were serious about opposing the politicized use of violence to inflict terror and devastation on civilian populations, the condemnation they seek would be directed towards the nuclear-armed state carrying out a genocide with the West’s unwavering moral and material support, not towards the besieged and occupied people lashing out in desperation against their colonial oppressor. They would be demanding not only that we condemn the naked brutality of Israel’s current assault on Gaza, but that we condemn the last 75 years of settler-colonial occupation, violence, and apartheid under the Zionist regime. The fact that no such demand is ever made, and that to even hint at such a demand in most mainstream spaces would elicit immediate accusations of antisemitism and terrorist sympathies, should tell us all that we need to know.

My point here is not that Hamas is beyond reproach, or that the left should simply accept atrocities against civilians—of the sort committed on October 7th—as inevitable and even justifiable. While I believe that any left politics worth its salt must be rooted in a principled commitment to the fundamental sanctity of all human life, I am not a pacifist—nor am I naive enough to pretend, in asserting my belief in Palestinians’ right to resistance, that it is somehow possible for any armed struggle to conducted in such a manner that there are no civilian casualties whatsoever. But that doesn’t mean I believe that one atrocity justifies another, nor do I buy the argument, employed in some fringe segments of the ‘decolonial’ online left with alarming frequency, that “there’s no such thing as an Israeli civilian.” The unquestionably settler-colonial nature of the Zionist project does not mean that every Israeli is a legitimate target, any more than the equally settler-colonial nature of the American project means that every American is fair game for violent reprisal by those whose people were enslaved and displaced and massacred throughout American history. If the left is unable to distinguish between complicity and culpability, if we are unable to distinguish between justice and retribution, then there is practically no one on Earth who is not at risk of being swept up in an ethic of revenge.

None of this changes the fact, however, that condemnation is a fool’s errand, or that the demand for condemnation is a rhetorical trap from which the left has no hope of escaping. Given the overwhelming scale of the repression that pro-Palestinian activists are facing at the moment, it’s understandable that some people would feel as though couching their rhetoric in the language of condemnation— “of course I condemn Hamas, but that doesn’t justify what Israel is doing”—might alleviate some of the pressure, and maybe even get others to take them more seriously.

The reality, however, is that what’s being demanded of us isn’t actually that we condemn Hamas—it’s that we fundamentally abdicate our solidarity with the Palestinian people altogether. No matter how measured we are in our criticisms of Israel, no matter how emphatically we preface our every word with condemnations of liberals’ and Zionists’ preferred bogeymen, even the most basic affirmations of Palestinian humanity will be seen as going too far. Any statement that doesn’t cleanly fit into the Zionist narrative of Israel as a beleaguered victim bravely defending itself against the subhuman hordes of barbaric Arab terrorists—really, anything short of an unqualified declaration of support for Israel’s absolute right to do whatever the hell it wants to whomever the hell it wants—will be taken as an admission of terrorist sympathies and closet antisemitism.

In other words, we’re damned if we do and damned if we don’t. In that case, it seems to me that instead of ceding precious rhetorical and political ground to bad-faith Zionist demands, we’re better off remaining steadfast and unequivocal in our commitment to the cause of Palestinian liberation, allowing the substance of our politics to speak for itself. When we are asked—as we inevitably will be—whether we condemn Hamas, we should reject the premise of the question itself rather than validating it with a “yes, but…” To respond otherwise is to reinforce the Manichaean logic of good and evil that is being used to paint the current violence in Gaza as a two-sided ‘conflict’ rather than a textbook case of colonial oppression and resistance—a logic which not only strips Palestinians of their humanity, but whose invocation only serves to provide further justification for their ongoing genocide. We have both a moral and political responsibility to resist that logic at all costs.

culture shock is a blog by the Indian-American writer, essayist, and cultural critic Pranay Somayajula. Click the button below to subscribe for free and receive new essays in your inbox:

So well articulates the views of so many. Thanks for writing it.